Contact Us in the UK

- Phone: 01302 811319

- Email:

- Mailing Address: 24 Elmfield Road, Hyde Park, Doncaster, South Yorkshire DN1 2BA

Contact Us in the US

- Phone: 202.468.4571

- Email:

- Mailing Address: PO Box 5188 Wheaton, IL 60189-5188

The other day I heard about the plight of a community in Hovd Province, in the far west of Mongolia. Their story is typical of that faced by so many in this vast, poverty-stricken country in the Central Asian steppe:

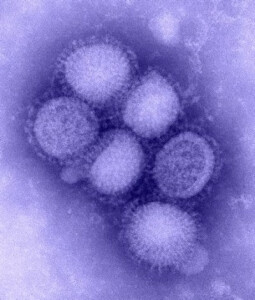

Schools have been shut here following the arrival of A/H1N1 swine flu. But in this particular community, there have been no recorded cases of the virus.

Yet the schools have been shut.

Many children there are dependent on the schools, not just for education, but for meals (hence nutrition), which they would otherwise go without. Closed schools means these children are at real risk of severe malnutrition or worse. It’s that stark. Factor in night-time temperatures down to -30C (no kidding), and I'll leave you to imagine how these folks are struggling to cope. And their situation is likely not unique. Hence a small risk of a very big problem (swine flu) has been translated into a very big risk of something that is ordinarily preventable. This is an irony. Yet it is the poor who are paying the price of this irony.

Micro-Enterprise Development, or MED as we refer to it in Radstock, is key to what we see as churches leading their communities out of poverty. Yet MED in this culture faces a number of challenges, challenges not dissimilar to those faced by Gospel work more generally in this struggling country:

Firstly, Mongols have grown used to being given things, and have come to view this as their way of relating to the wider world. Soviet-era development came from outside (the Soviet Union). And there was a lot of this development: the capital, where I live, is essentially a Russian city, inhabited mostly by Mongols. Virtually nothing remains of the Ulaanbaatar of a hundred years ago. But the USSR had no strategic interest in Mongolia being anything other than a grateful recipient of Moscow's largesse. Several generations came under this cultural 'footprint.' 20 years after the fall of communism here, this cultural dependence - or helplessness - continues, almost unabated. For incisive comment from a contemporary Mongolian economist, click here.

Secondly, many Mongols struggle with the idea that they can change their situations for the better. Things are as they are, 'because that is how it is,' is the mentality. This is rooted in the communist era here, with its apex set-up whereby a very few at the top called the shots, and the rest followed orders - or at least gave the appearance of doing so. But this fatalism is not just the fault of communism. The religious architecture here is heavily shaped by Buddhism and shamanism, which in their own ways, enforce the mentality of things being as they are, because that is how the spirits have arranged things. ‘Fate’ sits heavily on the culture. Even Christians struggle with this background mentality.

Thirdly, Mongolia is culturally nomadic, even though only around 600,000 out of a population of 2.7 million are directly involved in herding animals across the vast steppe and desert here. People's general response to adversity tends towards just picking up and moving on to the next thing, rather than sitting down to identify and solve the issues that caused the difficulties. You can imagine what that does in all kinds of situations, including for those trying to start businesses.

Lastly, Mongols tend to trust foreigners rather than each other - another throwback to the Soviet era. Without their secret police, the authorities could never know whether someone was being ‘faithful to the cause’ or just acting to please. And similarly, those outside the establishment often could not know who they were really talking to, since their neighbour in the next ger could be a secret police informer. Such mistrust persists, although it has morphed slightly in the new Mongolia.

There are other cultural challenges here too, which space does not allow us to explore here. But in micro-enterprise terms, all the above points to a real need, not just for teams to come in from outside and do small business training, which is great in itself. This need is for people to actually commit to living here, to inculcate Gospel business values into the culture, and develop further programmes as necessary, on the hoof. (In fact, there is no shortage of hooves here!I:-)) Seriously, there needs to be an incarnational approach, to complement teams coming from outside. Mongols place a high value on 'presence,' in other words, being here over the long term.

This is extremely sacrificial, but nowhere near as great as the sacrifice that caused Jesus to leave his Father's side and become incarnate among us and die for us. But it is incarnational nonetheless, and this is what will really effect change here, including unravelling vicious ironies like the one above.

For this reason, we would love to see a micro-enterprise specialist based with Radstock’s network churches in South Gobi. This is where we ran the initial MED module, using materials freely produced by Reconxile. Such a person or couple could help take forward the training, mentor the new business owners, and help cascade the training to others. We can't promise great material comfort, though you'll get some. But we can promise you the time of your life! If that sounds like you, do get in touch. If it sounds like someone else, do pass this on!

Comments

Login/Register to leave a comment